- Home

- Richard Zacks

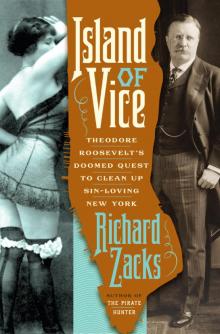

Island of Vice Page 3

Island of Vice Read online

Page 3

At a “tight house” on Bayard Street, the women wore nothing but body-hugging toe-to-neck tights and danced with a party of soldiers on leave from Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn.

Within a block of police headquarters, at 300 Mulberry Street, the trio encountered at least fifty prostitutes walking the streets. “I suppose none of the police officers in yonder building know what is happening,” commented Parkhurst dryly. Gardner was about to launch into a “wise up, Doc” speech when he realized the clergyman was kidding.

At the next joint, they witnessed a Bowery actress standing on her head while smoking a cigarette. She offered more private acrobatics for three dollars but they passed.

On Friday night March 11, 1892, Gardner delivered on his promise to show “something worse”…brothels and French circuses. Since several hundred brothels, mostly in nondescript walkup buildings, dotted the city, Gardner had plenty of options. He selected two of the city’s main redlight districts: the Tenderloin (19th Precinct) and the area south of Washington Square.

Gardner had chosen a wonderful meeting place—the Hoffman House bar. The now-forgotten Hoffman House was then the most famous bar in New York City. Guests entered on 24th Street just west of Madison Square Park and found themselves in a high-ceilinged private art gallery primarily featuring nudes, with marble and bronze statues of “Eve” and “Bacchus” and paintings such as Harem Princess. Seventeen bartenders worked each shift, squeezing fresh fruit into elaborate cocktails, pouring rare French wines or fifty-year-old brandy.

But it wasn’t the fine drinks, or even most of the artwork, that drew patrons, it was one painting, directly opposite the long mahogany bar, “unquestionably the biggest single advertisement any hotel in this country—probably in the world—ever had,” according to William F. Mulhall, a former manager.

The massive canvas, painted with almost photo realism by W. A. Bouguereau in 1873, seemed to invite viewers to climb into a lush erotic landscape. In the eight-foot-tall Nymphs and Satyr, four voluptuous, naked young women are seen trying to wrestle a playfully reluctant male into the cold water and over toward another cluster of naked nymphs on the far side of a stream. Highlighted and of dazzling whiteness, one callipygian goddess dominates the tug-of-war, and perhaps never has a luminous backside been viewed so adoringly by so many men with cocktails in hand.

Parkhurst was late. While waiting, Gardner noticed two large men, seated at a table, staring at them. Since his guided vice tour had been going on for a few days, he suspected that these two fellows might be plainclothes cops out to catch Dr. Parkhurst in some compromising position.

Gardner tried an experiment. He took Erving and walked out onto 24th Street to see whether the men would follow; indeed they did. Gardner, no rookie at surveillance, boarded the Sixth Avenue El at 28th Street, as did their pursuers. Gardner waited till the train was moving, yanked open the gate between the cars, and jumped off and happily watched the detectives sail by.

Gardner sent a boy with a message to Dr. Parkhurst to meet them instead at the St. James Hotel at Broadway and 26th Street, a place that attracted “sporting men” and actors. (“Sporting men” might be defined as men who gamble, drink, do not work regular hours, and are rarely seen in the company of their wives.)

They met Dr. Parkhurst at the nearby hotel. From there, they walked to a Tenderloin brothel chosen for its proximity to Parkhurst’s Madison Square Church. The threesome reached 33 East 27th Street around midnight, mounted the steps, and rang the bell. The building amid a row of attached buildings did not stand out. Hattie Adams, the madam, about forty-two years old, “a scraggly little thin woman” with curled “hay-colored” hair and wan green eyes, opened the door.

Gardner had slipped by earlier in the evening and said he would be returning with a friend, an “old man from the West” who had lost money gambling and needed cheering up. The three men—all well dressed enough to have been allowed in the Hoffman House—followed Mrs. Adams down a long dimly lit hallway to a comfortable back parlor, full of armchairs and sofas. Waiting there were seven young women—not garbed in the elaborate corseted, petticoated outfits of the era, but rather in “Mother Hubbards,” light simple dresses, low cut and reaching well above the ankle.

“This is rather a bright company,” said Dr. Parkhurst, with mock cheer. While the men waited for a servant to fetch beer—two large bottles—from a nearby saloon, Gardner bargained with Mrs. Adams for a “dance of nature,” eventually knocking the price to three dollars per girl for five girls.

One of the prostitutes blindfolded the seven-dollar-a-week piano player because “the girls refused to dance [naked] before him.” All was ready. Four of the five women then walked into the hallway and pulled a sliding curtain and undressed; the fifth just slipped behind an armchair. Removing a “Mother Hubbard” did not take long.

For the next fifteen minutes, to the piano plink of popular music, the nude women danced, sometimes alone, sometimes in pairs, wearing only stockings held up by garters. At one point, they linked arms for a brief nude Folies Bergère–style can-can. One of the naked girls, however, held aloof and refused to dance. “Hold up your hat!” she shouted to Gardner, who in turn yelled over to Parkhurst to toss him his black derby. Gardner stood up and held the derby about six feet off the ground. “The girl measured the distance with her eyes … and [she] then gave a single high kick, and amid applause sent the hat spinning away.”

Various naked girls then took turns, scissoring a leg ceilingward and launching a hat. Flesh jiggled; girls giggled; the sightless “professor” played. The eyes of the bashful Columbia College graduate Erving darted from the floor to wobbling nipples and thickets of hair, and then back to the floor; the young man was judged a world-class blusher. The naked women kept inviting the men to dance. Gardner claimed he couldn’t; Parkhurst refused, so once again Erving was drafted. Elegant in a “business suit,” Erving danced a waltz with a naked prostitute for about two minutes. He held her left hand and perched his right hand on her naked hip.

The girl who had refused to dance suggested nude leapfrog. To boisterous piano music, each of the women put her hands on the squatting girl in front and launched herself upward and forward, legs splayed for clearance. A giggling heap of bodies was often the result.

After the performance, the girls put back on what Dr. Parkhurst described as their “summer outfits.” A pair plunked themselves down on the laps of Gardner and Erving. They all kept whispering for the men to mount the stairs to the bedrooms. But the group drank one more round of beer, then left around 12:45 a.m., with Hattie Adams bidding them to come again.

They walked south about a mile through the cold night streets—some lit by gas, others by Edison arc lamps—discussing what they had seen; along the way, a friend of Gardner’s, a smallish young tailor-turned-detective named William Howes, joined them, as an extra eyewitness. Gardner, promising “something worse,” took them to the Golden Rule Pleasure Club on West 3rd Street. They opened the door to the basement of the four-story brick house and an electric buzzer alerted the hosts of their arrival. “Scotch Ann,” a tall graceful woman, greeted them.

She guided them down a hallway that led to a cluster of small open-doored rooms, each with a table and couple of chairs. The men peered inside; they saw in each “a youth, whose face was painted, eyebrows blackened and whose airs were those of a young girl.” They overheard the “youths” talking in a “high falsetto voice” and calling each other “by women’s names.”

Gardner whispered to Dr. Parkhurst that these “women” were men, that they were in a cross-dressing homosexual brothel. Parkhurst rushed through the hall, up the steps, and back out to the street. “I wouldn’t stay in that house for all the money in the world,” he told Gardner.

The tour group then wandered around so-called Frenchtown, the French brothel district of Wooster, Greene, and West 3rd and 4th Streets, today’s New York University campus. With Gardner in the lead, the four men climbed the stone steps of a two-story ho

use on West 3rd Street and found six young scantily clad women ranged along the side of a hallway, “pretty, painted, powdered and dissipated looking.” The filles, in sleeveless gauzy frocks despite the cold, were speaking French and Dr. Parkhurst surprised them by joining in. “Whatever the Doctor said seemed to please the women immensely,” later recalled Gardner.

As soon as they entered the parlor and picked out armchairs, “one of the girls, the plumpest and best looking in the lot, sat down on the doctor’s lap.” Parkhurst implored Gardner with his eyes to help him. (To get some idea of the heft, Sylvia Starr, a vaudeville actress then playing American Venus, stood five feet five inches and weighed 151 pounds, with a thirty-two-inch waist.) Gardner, amused, hesitated a long minute or two, then eventually beckoned the girl over to him. They drank some beer and left to go to another brothel.

Now came the climax of Dr. Parkhurst’s sin tour: the French Circus at Marie Andrea’s.

The four men walked to 42 West 4th Street and a woman in an upper window of the three-story brick house whistled down to them. A nightstick-twirling policeman stood nearby and apparently heard and saw nothing. They rang. Marie Andrea, a plump older French woman with small dark eyes, who spoke broken English, opened the door and greeted them. She guided them into a parlor on the left. They asked for music; she replied that she had something better: a “French Circus.” She demanded five dollars per man with a trip upstairs included in the price, but Gardner bargained her down to four dollars each, with an extra performer thrown in.

Madame Andrea gave her orders in French. “A bevy of young and decidedly pretty French women trooped into the room,” Gardner wrote. “All of them wore the Mother Hubbard costume, of silk and gay satin, with stockings and shoes.”

Each of the men could select a girl; Parkhurst chose first and perhaps out of compassion chose a “thin scrawny consumptive looking girl” about sixteen years old. Since the girls spoke only French, there was little conversation as the other three men made their selections.

All the women trooped out; Marie Andrea attempted to describe in Franglais the upcoming acts; five women returned naked except for stockings.

So what exactly did Reverend Parkhurst and his three colleagues see that night? Charlie Gardner refused to reveal it in his book; Parkhurst also declined in his Our Fight with Tammany. The newspapers later drew a veil over the incident, the New York Sun calling “most of the testimony … unprintable.”

But the New York World gave a subtle hint. The paper stated that a defense lawyer for the prostitutes later considered charging Reverend Parkhurst with violating Sections 29 and 303 of the New York State Penal Code. Section 29 concerned “aiding and abetting” someone in the commission of a crime. And a glance at the New York State law code reveals that Section 303, “Sodomy,” states: “A person who carnally knows in any manner any animal or bird, or carnally knows any male or female person by the anus or by or with the mouth or voluntarily submits to such carnal knowledge, or attempts intercourse with a dead body, is guilty of sodomy and is punishable with imprisonment for not more than twenty years.” A French circus featured oral sex. In the 1890s, men went to French brothels for oral sex, which was generally not available elsewhere. In this case, two of those French prostitutes performed cunnilingus.

The five French women at Madame Marie Andrea’s finished their performance around 1 a.m. that night and “bowed and smiled like a successful lot of ballet dancers,” according to Gardner. Servants hauled away the yellow cloth. The naked women sat on the clothed laps of all but Parkhurst.

The men stayed for their fourth one-dollar round of beers but passed on their trip upstairs. Once outside the building Parkhurst called it “the most brutal, most horrible exhibition that I ever saw in my life.”

Just thirty hours after leaving Marie Andrea’s, Parkhurst mounted the pulpit on Sunday, March 13, 1892, and lashed back at Tammany for accusing him of ignorance and charging him with libel. His theme was “The Wicked Walk on Every Side, When the Vilest Men are Exalted.”

“Don’t tell me I don’t know what I am talking about,” he told his congregation. He announced that he had the addresses of thirty houses of prostitution within blocks of the church. “Many a long dismal heart-sickening night, in company with two trusty friends, have I spent … going down into the disgusting depths of this Tammany-debauched town and it is rotten with a rottenness that is unspeakable and indescribable.”

He explained: “To say that the police do not know what is going on and where it is going on … is rot … Anyone who with all the easily discernible facts in view, denies that drunkenness, gambling and licentiousness in this town are municipally protected, is either a knave or an idiot.” He apologized for his frank language.

Reverend Parkhurst said he had been wincing under Tammany’s criticisms and the criticisms of some fellow ministers. Now he was delivering to the district attorney 284 addresses of gambling joints, brothels, and after-hours saloons. His last line: “Now what are you going to do with them?”

After some hesitation, the district attorney, engulfed by so much publicity, brought disorderly house charges against four brothel madams visited by Parkhurst, including Hattie Adams and Marie Andrea.

The official’s unexpressed goal seemed to be to inflict as much embarrassment as possible on Parkhurst in the process so the minister would not go snooping again. The press happily helped. Headlines ran: parkhuRST’S CAN CAN and PARKHURST’S SIGHT-SEEING.

Hattie Adams hired the leading team of criminal lawyers in the city: gargantuan William Howe “wearing a constellation of diamonds” and small shiny-domed Abe Hummel. “I do not know that I ever felt so much my inability to express my loathing and disgust for any man as I do for Parkhurst,” said Howe. “In the words of M. Thiers, ‘I cannot elevate him to the level of my contempt.’ ”

Hattie Adams claimed to run a boardinghouse that because of the neighborhood attracted mostly “actors and bicycle men and women” (i.e., traveling people). She was asked: “Are your guests single women?” She replied: “Not particularly single.” But Adams was adamant that the Parkhurst party had arrived and asked for one of her boarders, a Miss Devoe, who had provided all the entertainment.

The defense trotted out another of those boarders, Charlotte Vanderveer, a “hatchet-faced” curly-haired brunette, who claimed to be Adams’s seamstress. She testified that Dr. Parkhurst grabbed her “here” (indicating her bosom) and ripped her dress. “Now you undress and I’ll pay you well for it,” she quoted the minister as saying.

Parkhurst kept a steely calm both inside the courtroom and out.

Heir John L. Erving had a harder time. (Dr. Parkhurst had once dubbed him a “human sunbeam” because vice did not contaminate him. The nickname stuck when the newspaper boys shortened it to “Sunbeam.”)

Q: Did [the naked dancer] put her arm around your neck?

A: No.

Q: Did she kiss you?

A: No, not then.

Q: When did she kiss you?

A: As I got up to go, she put her arms around my neck and kissed me.

The New York World reported that the blond Erving blushed so intensely it almost seemed as though he were bleeding. After testifying he collapsed and began muttering: “Where am I? What day is it?” He was quickly hauled away in a carriage.

A doctor at his parents’ home in Rye, New York, diagnosed “extreme nervous prostration” and he was not allowed to return to the court, damaging the case against two other brothels. “What a sad picture we have here,” said one of the defense lawyers. “This minister of the gospel taking the spotless youth from brothel to brothel, from orgy to orgy, merely to illustrate the existence of vice.”

Despite expensive legal counsel, the two madams were convicted in May 1892; the judge sentenced Hattie Adams to nine months on Blackwell’s Island, Marie Andrea to a year and a $1,000 fine. (Apparently, even a whiff of oral sex/French vice boosted the punishment.)

Parkhurst’s Society for the Prevention

of Crime was now riding high. Its detectives, including Gardner, then submitted affidavits to the district attorney against hundreds of brothels, gambling joints, and law-breaking saloons. Two Parkhurst detectives visited twenty-five brothels in the Tenderloin in twenty-four hours.

The Society also gathered evidence about saloons open on Sunday, hiring four detectives and giving them $50 in dimes to buy drinks. The men sipped beers in 254 saloons open after hours and on the Lord’s day. “[Dr. Parkhurst] made the point that we four men had certainly sharper eyes than the 3,000 policemen or so in the city,” Gardner later wrote.

That summer and in the months following, Tammany sweated; with so much scrutiny, the district attorney was forced to bring cases to trial, and police captains found it hard to ignore vice. The great corrupt money machine was clogged; the great lewd swaggering town was forced to be discreet, like a Philadelphia or even shut down like a Boston. Parkhurst, though criticized for slumming it a bit too enthusiastically, was looking triumphant.

Enter “Big Bill” Devery.

The Tammany police captain found out that Charlie Gardner, the lead detective for Parkhurst’s Society, was investigating a prostitute in his 47th Street precinct. What if “Big Bill”—who stood five feet ten and weighed 225 pounds, with a fifty-inch waist and size seventeen shoes—discovered that the reform detective was trying to shake her down for a bribe? Demanding dollars to drop the whole thing? “All these amateur societies fall into the hands of blackmailers,” Devery once complained, without a trace of irony. Then Devery could disgrace high-flying Parkhurst of Madison Square and could free Tammany from the endless meddling of these oh-so-pure reformers. And if Captain Devery couldn’t catch Detective Gardner in the act, he could always frame the man.

“I seen my opportunities and I took ’em,” as Tammany’s George Washington Plunkitt once said.

Julius Caesar had his Rubicon; Big Bill Devery had a hooker and a sloppy private eye.

Island of Vice

Island of Vice