- Home

- Richard Zacks

Island of Vice

Island of Vice Read online

Copyright © 2012 by Richard Zacks

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This page and this page constitute an extension of this copyright page.

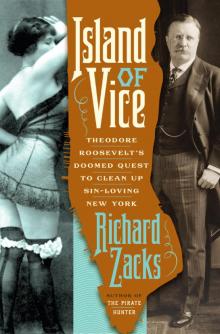

Cover design by Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich

Cover photograph of the woman: © The Granger Collection, New York

Cover photograph of Roosevelt: © Apic / Getty Images

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Zacks, Richard.

Island of vice : Theodore Roosevelt’s doomed quest to clean up sin-loving

New York / Richard Zacks. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Vice control—New York (State)—New York—History—19th century.

2. Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858–1919. 3. Police administration—New York

(State)—New York—History—19th century. 4. New York (N.Y.)—

Moral conditions—History—19th century. 5. New York (N.Y.)—Social

life and customs—19th century. I. Title.

HV6795.N5Z33 2012

363.2′309747109034—dc23

2011028586

eISBN: 978-0-385-53402-4

v3.1_r2

For Georgia and Ziggy

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PROLOGUE

1 • PARKHURST AND THE SIN TOUR

2 • THE STING

3 • THE REWARD

4 • POLICE ON THE GRILL

5 • ENTER CRUSADER ROOSEVELT

6 • SLAYING THE DRAGONS

7 • MIDNIGHT RAMBLES

8 • THIRSTY CITY

9 • ELLIOTT

10 • LONG HOT THIRSTY SUMMER

11 • THE ELECTION

12 • CRACK UP … CRACK DOWN

13 • CHRISTMAS: ARMED AND DANGEROUS

14 • I AM RIGHT

15 • DEVERY ON TRIAL

16 • SURPRISES

17 • DUEL

18 • BACK IN BLUE

19 • PARKER TRIAL

20 • RESTLESS SUMMER

21 • CAMPAIGNING FOR MCKINLEY AND HIMSELF

22 • BELLY DANCERS AND SNOW BALLS

23 • WHERE’S THE EXIT?

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ILLUSTRATIONS

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

stunningly beautiful woman stood at the highest point of the Manhattan skyline. She was naked, perched on her tiptoes at the very top of the tower of Madison Square Garden at 26th Street, more than 300 feet off the ground. Fifty Edison lamps lit her up, revealing slim adolescent hips, pomegranate breasts, a hairless cleft. Late-night revelers staggering home from the taverns and clubs tipped their hats to her.

The woman’s name was Diana. She was a thirteen-foot gilded copper statue of the Roman goddess of the hunt. Lovely Diana, virginal goddess, towered over the surrounding five-story buildings. Guidebooks touted her as drawing as many visitors as that clothed giantess of liberty in the harbor. Perfectly balanced on ball bearings, the statue could spin. For more than a decade, Diana’s breasts and outstretched arm revealed the direction of the winds. New Yorkers knew that nipples pointing uptown meant breezes to the north.

Architect Stanford White had paid for her out of his own pocket and demanded a pubescent body that matched his desires. Famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens—better known for his equestrian heroes—had modeled this, his only nude female statue, after his young mistress, Julia Baird.

Under the respectable cloak of neoclassical art, Diana was the sly insider joke of these two famous men, a museum-worthy tribute to forbidden lust. And so she was the perfect symbol of New York in the 1890s, a city of silk top hats on Wall Street and sixteen-year-old prostitutes trawling Broadway in floor-length dresses, of platitudes uptown and bawdy lyrics on the Bowery, of Metropolitan Opera divas performing Wagner and of harem-pantsed hoochie-coochie dancers grinding their hips on concert saloon stages.

Manhattan, then growing in prestige by the minute, rated handfuls of superlatives: nation’s financial capital (Wall Street), nation’s leading commercial port (144 piers), dominant manufacturing center (12,000 factories and 500,000 workers), arts capital (museums and 100 theaters delivering a forty-week season), nation’s premier residential address (Fifth Avenue), philanthropic center, cosmopolitan melting pot.

Almost two million people lived here, the wealthiest and the poorest crammed onto about a dozen square miles of one ideally situated island, with many neighborhoods joined by a mere five-cent cable car ride. The city housed more Irish than Dublin, more Germans than any city but Berlin, with pockets of Syrians, Turks, Chinese, Armenians, and with a new steady influx of Italians and Russians. The polyglot babble of the streets dizzied the minds of fifth-generation Americans. While the upper crust aimed at a stagey British enunciation, à la the characters of Henry James and Edith Wharton, the poor of New York garbled the language into a street slang that often required interpretation. When Billy McGlory, a notorious saloon keeper, testified about a prostitute stealing a man’s wallet and refusing to give it back, he said under oath in a courtroom: “If the bloody bitch had turned up the leather, I wouldn’t be in this trouble. It’s the first time I ever called a copper in my house on a squeal and I get it in the neck for trying to do what’s right.”

New York was a thousand cities masquerading as one. Its noise, vitality, desperation, opulence, hunger all struck visitors. Department stores such as Stern’s straddled city blocks; telephone companies linked 15,000 wealthy private customers. Convicted vagrants served time in workhouses on Blackwell’s Island. Columbia College bought the land of the Bloomingdale Lunatic Asylum for a new uptown campus. The poorer districts smelled of sweat and horse manure. Many tenements had courtyard outhouses. The poorest slept in shifts. Uptown near Central Park, liveried servants helped veiled ladies into black enameled coaches, some bearing family coats of arms acquired by marrying European princes.

Not a single traffic light or even a stop sign regulated the mad flow of tens of thousands of horses, carriages, wagons, public horse and cable cars. Anarchy ruled the corners, and foreigners complained about the dangers of crossing busy streets. New York wagon drivers, paid for speed, cursed in many languages. Vehicles could ride in any direction on any street. The five-mile-per-hour speed limit was routinely ignored; the only faint attempt to aid pedestrians trying to dart across the streets was a squad of two dozen tall policemen stationed at major Broadway intersections.

Thieves stole more horses in New York City than in the entire state of California or Texas, and then raced to outlaw stables scattered around town—the equivalent of modern-day “chop shops”—to quick-dye horses’ coats from dappled gray to black, clip tails, and repaint wagons. Four massive elevated train lines—on Second, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Avenues—striped the island north and south, casting shadows and coal ash, and allowing intimate glimpses into second-story apartments.

Above all, New York reigned as the vice capital of the United States, dangling more opportunities for prostitution, gambling, and all-night drinking than any other city in the United States.

A man with a letch, a thirst, or an urge to gamble could easily fill it night or day. Saloon owners, such as Mike Callahan, tossed their keys in the East River and never locked

up. Richard Canfield ran his elegant casino—recommended guests only—at 22 West 26th Street, under the shadow of Diana. Swells in frock coats played faro and roulette for thousands, with no money exchanged, only elegant inlaid-ivory chips gliding across tables. A four-star chef waited in the basement for dinner orders. Other gamblers, wanting to bet on horse races as far away as New Orleans, could find “pool rooms” with telegraph tickers in the second floors of saloons and back rooms of hotels.

More than 30,000 prostitutes worked daily, from the expensive soubrettes of the Tenderloin brothels to the impoverished Russian Jewish girls charging fifty cents down on Eldridge Street. No man could walk far at night without being propositioned by a streetwalker. One do-gooder doing the math estimated that each prostitute averaged four clients a day and that on most days one out of every six adult men in New York City paid for sex with a prostitute. “The traffic in female virtue is as much a regular business, systematically carried on for gain, in the city of New York,” conceded Thomas Byrnes, the city’s leading police detective, “as is the trade in boots, and shoes, dry goods and groceries.”

At a trial in 1895 of a police captain accused of sheltering brothels, a witness, a magazine illustrator named Charles Higby, recounted that his studio on 14th Street overlooked a seedy hotel used by streetwalkers. “What did you see? Tell us exactly,” he was asked. “Fornication. Three windows at a time,” he replied, adding that during the “intermission” a maid changed the sheets. Prosecutor: “Was it not offensive to you to see these different couples going in there and fornicating?” Higby: “Sometimes, [but] sometimes very amusing.”

Around this time, French prostitutes in New York began offering oral sex, a taboo-in-America pleasure that cost twice the price of intercourse. Peddlers sold French postcards; gents went to audio parlors and paid a nickel to hear music or dirty jokes. (“She’s a ballet dancer; first she dances on one leg, then on the other; between the two she makes a living.”)

The Tenderloin, the most popular public vice district of the fin de siècle city, was a two-block-wide swath on either side of Broadway from 23rd Street to 42nd Street. Dance halls such as the Star & Garter and Haymarket, with orchestras playing waltzes, charged twenty-five cents admission for men; women entered free.

One song, with a cloying melody, ran:

Lobsters! rarebits! plenty of Pilsener beer!

Plenty of girls to help you drink the best of cheer;

Dark girls, blond girls, and never a one that’s true;

You get them all in the Tenderloin when the clock strikes two.

Your heart is as light as a butterfly,

Tho’ your wife may be waiting up for you;

But you never borrow trouble in the Tenderloin

In the morning when the clock strikes two.

New York City was the Island of Vice.

And then suddenly in 1894, after a series of particularly ugly police scandals involving brutality and shakedowns of even bootblacks and pushcart peddlers, Tammany lost the mayor’s election.

And the new mayor, independent-minded William L. Strong, appointed Theodore Roosevelt as a police commissioner on May 6, 1895, with the understanding that Roosevelt, a law-and-order Republican, would be elected president of the four-man Police Board, the highest-ranking police official. It was a respectable return for the New York City native, whose career was petering out in a bureaucratic post in Washington, D.C., and whose books were never best-sellers.

Theodore Roosevelt was then a work-in-progress, years removed from San Juan Hill and the White House. He was energetic, stubborn, opinionated, with a fondness for manliness—boxing, hunting, military history—and a knack for head-on collisions with allies and enemies alike. “He was tremendously excitable, unusually endowed with emotional feeling and nervous energy,” said William Muldoon, who lived not far from him on Long Island Sound, “and I believe his life was a continual effort to control himself.”

Roosevelt (“Theodore” to his wife and friends, never “Teddy”) was born into one of the city’s wealthiest families. His Dutch ancestors had parlayed a hardware and plate-glass business into a real estate and banking empire; his namesake father had inherited the then staggering sum of $1 million in 1871.

After finishing his studies at Harvard, Roosevelt had dedicated himself to a career in writing and reform politics. He had served three years in the gritty New York State Assembly fighting Tammany Hall and boodle and kickbacks.

He lost his mother and first wife on the same day in 1884, salved his soul in the Dakotas, then was defeated for mayor in 1886. His reputation as an uncompromising reformer drew catcalls from the seedier elements of the city. Abe Hummel, a criminal lawyer, said Roosevelt’s tombstone should read: “Here lies all the civic virtue there ever was.”

Roosevelt had spent the last six years working in semi-obscurity on the Civil Service Commission in Washington. Clearly, that obscurity had chafed him.

“He went everywhere,” wrote the Washington Post of those years, “pervaded the whole official atmosphere, turned up where he was least expected, bullied, remonstrated, criticized and denounced by turns. Never quiet, always in motion, perpetually bristling with plans, suggestions, interference, expostulation, he was the incarnation of bounce, the apotheosis of inquisition.”

The thirty-six-year-old family man now had four young children—Ted Jr., Kermit, Ethel, Archie—to go with eleven-year-old Alice from his first marriage. He and his wife, Edith, had been maintaining a house in D.C. and one in Oyster Bay, and despite income from his inheritance and fees from his six books (such as the 541-page War of 1812) and numerous magazine articles, he was having trouble paying his bills.

Roosevelt in 1895 was an outspoken crusader for a vast array of causes that would decades later be bannered under the umbrella of progressive reform, a term then unknown. He wore thick pince-nez glasses, stood five feet nine, often dressed nattily; he had a knight-errant quality about him, eager to call out the frivolous rich, the lazy poor, the sleazy politicians.

Reformers in New York City were ecstatic at his police appointment. Everyone expected the fight to be tough and some thought it might be made even tougher by the man undertaking it. “There is very little ease where Theodore Roosevelt leads,” conceded his longtime friend and future biographer, Jacob Riis.

Roosevelt had returned home to clean up the Island of Vice.

he battle started with a poorly researched sermon.

The Reverend Charles H. Parkhurst, adorned with an abundant goatee and steel-rimmed, thick-lensed glasses, just shy of his fiftieth birthday, stood on February 14, 1892, before about 800 well-dressed parishioners in Madison Square Presbyterian Church, at 24th Street off the park. The understated building—a long and narrow slab of drab brownstone with a classic steeple—evoked earnestness, in stark contrast to the exuberant yellow-and-white Madison Square Garden tower nearby, topped by nude spinning Diana. In the pews sat the city’s elite; scrubbed boys and girls fidgeted but their parents certainly did not, not that morning.

Parkhurst sent no advance notice of the subject of his sermon nor did he distribute the text to the press during the prior week, but afterward almost every newspaper requested it.

Parkhurst didn’t thunder from the pulpit. He spoke evenly and favored erudite words, befitting an Amherst graduate (class of 1866), one who had studied abroad at Leipzig and once penned an essay on similarities between Latin and Sanskrit verbs. He sometimes showed a sly dry wit.

On that Sunday winter morning, his calmly delivered words stunned his audience. He called the Tammany men ruling New York, especially the mayor, the district attorney, and the police captains, “a lying, perjured, rum-soaked and libidinous lot.” He accused them of licensing crime, of polluting the city for profit. He said he would “not be surprised to know that every building in this town in which gambling or prostitution or the illicit sale of liquor is carried on has immunity secured to it by a scale of police taxation” as “systematized” as the local re

al estate taxes. He asserted “your average police captain is not going to disturb a criminal if the criminal has means.”

Parkhurst was born on a farm outside Framingham, Massachusetts; he revered his rural roots. He had never seen vice until he moved to the big city. He taught school till age thirty-three. For the past dozen years at Madison Square Presbyterian he had been praised for geniality and charitable works but was little known outside his congregation.

That would change overnight.

The minister, his quiet cadence building, wrapped his sermon in a biblical theme, charging that gambling places “flourish on all these streets almost as thick as roses in Sharon,” that day or night, “our best and most promising young men” waste hours in those “nefarious dens.” He said he had firsthand experience that the city government “shows no genius in ferreting out crime, prosecutes only when it has to, and has a mind so keenly judicial that almost no amount of evidence that can be heaped up is accepted as sufficient to warrant indictment.”

He explained that, as the president of the Society for the Prevention of Crime, he had recently met with the district attorney and confronted him about McGlory’s—a notorious den of prostitutes and thieves that thrived for years. The D.A. had replied that he had no idea that such “vile institutions” existed. “Innocence like that,” added Dr. Parkhurst, “in so wicked a town ought not to be allowed to go abroad after dark.”

Parkhurst promised his rapt congregation that he was not speaking as a Democrat or a Republican but as a Christian. He complained that the word protest was no longer driving “Protestants.” He called for action.

“Every effort that is made to improve character in this city, every effort to make men respectable, honest, temperate and sexually clean is a direct blow between the eyes of the Mayor and his whole gang of drunken and lecherous subordinates.”

Tammany Hall was a vast Democratic political club, a confederacy of strivers that had ruled the city since the late 1860s. The organization blessed lawbreaking mostly of a victimless nature in exchange for a payoff. Cops, many with Irish accents, closed their eyes, and police captains and Tammany grew rich with the blindness. The annual rakeoff totaled in the millions of dollars, back when the average annual wage topped out at $500 or less. The boodle was breathtaking. All the while, the great city, growing into a cosmopolitan masterpiece, prospered, with lip-service platitudes about morality by cynical Tammany Hall orators and everyday embrace of vice.

Island of Vice

Island of Vice